Bitte anklicken. Quelle: Wikipedia

Warum? Warum dreht sich der auf einmal?

Klar: Erhaltung des Drehmoments. Soweit wussten das alle. Allerdings geht’s genaugenommen um den Drehimpuls, gleich unten, einen Pseudovektor.

Das Drehmoment, bekant vom Hebelgesetz aus der Schule und ab achtzehn vielleicht von Radmuttern, ist zwar zunächst eine skalare Größe (kein Vektor) in mkg, Kraft (hier altmodisch in kg) mal Hebelarm (m). Moderner liest sich das hier etwa so: »Bei Pkw ist meist ein Drehmoment von zwischen 100 und 200 Newtonmeter (Nm) in der technischen Dokumentation spezifiziert.« Für mich wären das griffigere 10 bis 20 mkg, richtiger 10,1972 bis 20,9343 kpm, Kilopondmeter, was aber zuweit und abseits führt.

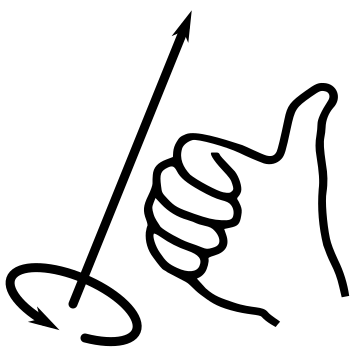

Als Vektor gibt’s das Drehmoment auch.

|

| Rechte-Hand-Regel, wieder Wikipedia |

Zurück also zum Drehimpuls. Rot im Video ist der Drehimpulsvektor des Rades, nach oben, und der ist ordentlich groß, weil sich das Rad zu Beginn ja schnell dreht. Gelb ist der Drehimpuls des Schemels, und der ist erst einmal Null, weil der Knabe geduldig normal dasitzt.

Erklärungsversuche, die die resultierenden Drehrichtungen aufzeigen, fand ich wenige – jedenfalls keine einfachen. In der Schule wusste das spontan auch keiner.

Am besten gefallen hat mir eine Erklärung aus Amerika, hier. Erstmal englisch, dann übertragen.

In the bicycle wheel gyroscope demonstration, there are two possible turning motions. The platform the person stands on turns like a wheel on its side. Call this horizontal turning motion. The other turning motion is the bicycle wheel the person is holding. Initially it is vertical, as a bicycle wheel normally stands. Call this vertical turning motion.

To begin with, someone spins the bicycle wheel. There is vertical turning motion in the bicycle wheel, but no horizontal turning motion of the platform. Then the person tilts the bicycle wheel to the side, so now there is horizontal turning motion where there wasn’t any before. Conservation of angular momentum tries to fix this. The platform starts spinning in the direction opposite that of the bicycle wheel. If you add the backward turning of the platform and the forward turning of the bike wheel together, you get zero. So horizontal motion is the same as when we started: nothing. When the bike wheel is tilted back vertically, the platform stops spinning, as in the beginning.

Also:

Im Experiment gibt’s zwei mögliche Drehungen, die des Rades und die vom drehbaren Sitz. Die Drehung des Rades ist zunächst senkrecht, wie beim Fahrrad etwa. Der Sitz kann sich nur waagrecht drehen, tut das aber anfangs nicht. Andere Drehungen sind nicht möglich (sieht man vom kurzzeitigen Kippen ab).

Kippt man jetzt das drehende Rad, so »teilt« sich dessen Drehbewegung in eine immer größer werdende waagrechte und eine geringer werdende senkrechte Drehbewegung. Die senkrechte »hat Pech gehabt«, die waagrechte Komponente wird ausgeglichen durch die neu entstandene Drehung des Sitzes, damit in Summe waagrecht wieder Null herauskommt.

Der Sitz dreht sich andersherum als das Rad: Bei sich gegen den Uhrzeiger drehendem Rad (von der linken Hand her gesehen) schwenkt der Sitz nach rechts, also im Uhrzeigersinn. Solange das Rad nicht in die senkrechte Ausgangslage zurückversetzt wird, dreht sich der Sitz weiter.

Kommt er in die Ursprunglage zurück, oder kann seine Drehung früher oder später enden? Ich meine ja, denn nicht die Lage ist »geschützt«, nur der Drehimpuls.

Die Menge der bewegten Masse spielt natürlich auch eine große Rolle (besonders bei diesen Herren im Bild). Da gleicht schon ein wenig Schemeldrehung viel Raddrehung aus.

Damit wäre die Sache wohl geklärt. Es geht aber auch umständlicher.

Eine erste Erklärung findet man bei der Präzession: »Wenn beim rotierenden Kreisel versucht wird, seine Rotationsachse zu kippen, dann zeigt sich eine Kraftwirkung senkrecht zur Kipprichtung der Rotationsachse.«

Der aus zwei Drehungen resultierende Drehimpuls ist (meine ich) ein Kreuzprodukt. Usw.

Hier genauer und anschaulicher, aber halt englisch:

Fig. 20–1.Before: axis is horizontal; moment about vertical

axis = 0.

After: axis is vertical; momentum about vertical axis is still zero;

man and chair spin in direction opposite to spin of the wheel.

Let us now return to the law of conservation of angular momentum. This law may be demonstrated with a rapidly spinning wheel, or gyroscope, as follows (see Fig. 20–1). If we sit on a swivel chair and hold the spinning wheel with its axis horizontal, the wheel has an angular momentum about the horizontal axis. Angular momentum around a vertical axis cannot change because of the (frictionless) pivot of the chair, so if we turn the axis of the wheel into the vertical, then the wheel would have angular momentum about the vertical axis, because it is now spinning about this axis. But the system (wheel, ourself, and chair) cannot have a vertical component, so we and the chair have to turn in the direction opposite to the spin of the wheel, to balance it.

After: axis is vertical; momentum about vertical axis is still zero;

man and chair spin in direction opposite to spin of the wheel.

Let us now return to the law of conservation of angular momentum. This law may be demonstrated with a rapidly spinning wheel, or gyroscope, as follows (see Fig. 20–1). If we sit on a swivel chair and hold the spinning wheel with its axis horizontal, the wheel has an angular momentum about the horizontal axis. Angular momentum around a vertical axis cannot change because of the (frictionless) pivot of the chair, so if we turn the axis of the wheel into the vertical, then the wheel would have angular momentum about the vertical axis, because it is now spinning about this axis. But the system (wheel, ourself, and chair) cannot have a vertical component, so we and the chair have to turn in the direction opposite to the spin of the wheel, to balance it.

First let us analyze in more detail the thing we have just described. What is surprising, and what we must understand, is the origin of the forces which turn us and the chair around as we turn the axis of the gyroscope toward the vertical. Figure 20–2 shows the wheel spinning rapidly about the y-axis. Therefore its angular velocity is about that axis and, it turns out, its angular momentum is likewise in that direction. Now suppose that we wish to rotate the wheel about the x-axis at a small angular velocity Ω; what forces are required? After a short time Δt, the axis has turned to a new position, tilted at an angle Δθ with the horizontal. Since the major part of the angular momentum is due to the spin on the axis (very little is contributed by the slow turning), we see that the angular momentum vector has changed. What is the change in angular momentum? The angular momentum does not change in magnitude, but it does change in direction by an amount Δθ. The magnitude of the vector ΔL is thus ΔL=L0Δθ, so that the torque, which is the time rate of change of the angular momentum, is τ=ΔL/Δt=L0Δθ/Δt=L0Ω. Taking the directions of the various quantities into account, we see that

τ=Ω×L0. (20.15)

Thus, if Ω and L0 are both horizontal, as shown in the figure, τ is vertical. To produce such a torque, horizontal forces F and −F must be applied at the ends of the axle. How are these forces applied? By our hands, as we try to rotate the axis of the wheel into the vertical direction. But Newton’s Third Law demands that equal and opposite forces (and equal and opposite torques) act on us. This causes us to rotate in the opposite sense about the vertical axis z.

τ=Ω×L0. (20.15)

Thus, if Ω and L0 are both horizontal, as shown in the figure, τ is vertical. To produce such a torque, horizontal forces F and −F must be applied at the ends of the axle. How are these forces applied? By our hands, as we try to rotate the axis of the wheel into the vertical direction. But Newton’s Third Law demands that equal and opposite forces (and equal and opposite torques) act on us. This causes us to rotate in the opposite sense about the vertical axis z.

• ETH: Grosser kardanischer Kreisel auf Drehschemel

• Corioliskraft

• Link hierher (zum Weitegeben):

http://blogabissl.blogspot.com/2015/11/drehschemelexperiment-drehimpuls-seine.html

Warum, Papa, fragst du warum?

Zugabe:

| Quelle |

Noch eine Zugabe: »Teufelsrad« – Wikipedia – Oltoberfest

Und noch was Schönes, gibt’s auch für Smartphones als »Deckel«.

| Paolo Čerić |

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen